Views of houses in Delft

Johannes Vermeer

known as „The Little Street„

by martin.

OVERVIEW I

unusual /

remarkable

A house in a little street.

At first glance, this painting doesn’t seem very special, right? It reads like a cute, small, almost naive study of a few houses and it certainly doesn’t look like what most people today expect from one of the great Dutch masters: Johannes Vermeer.

That’s exactly what makes it unusual. It shows (just) a quiet row of houses: a slice of a narrow street in Delft, in the south-west of the Netherlands. If you give yourself a moment with it, the scene feels calm and perfectly balanced. Then your eyes probably start drifting toward the details: rough bricks, colourful window shutters, tiny cracks in the walls you can almost feel with your fingertips. You look up at the sky, more houses begin to emerge from the background and then there are, of course, the people. Let’s explore this painting together. Be assured: it is remarkable.

Facts & Data

Artist

Johannes Vermeer

Oldest documented title

„Gezicht op huizen in Delft“

(„Views of houses in Delft“)

Today known as

„Het Straatje“

(„The Little Street“)

Dimensions

Height 54.3 cm x width 44 cm

Materials

Oil on canvas

Creation

Dated around 1658

On view at

Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

OVERVIEW II

the

painter

It is impossible to tell every detail of a Vermeer painting, or any painting for that matter, in just one blog article. Instead I want to give an overview of the painting that today is called The Little Street („Het Straatje“). For context, I also want to include a basic introduction to Vermeer himself.

Johannes Vermeer (baptized 31 October 1632, Delft as Joannis van der Meer; buried 15 December 1675, same place) is probably best known for his intimate indoor scenes of everyday life, his astonishing sensitivity to light, colour and atmosphere. According to current knowledge, his oeuvre—his complete body of work—comprises just 34 paintings that can be attributed to him with certainty, and most of them are difficult to date. For his time and status, that is remarkably little: essentially a very slow painting pace. For comparison, painters like Frans Hals, Gerard ter Borch, or Pieter de Hooch produced two to three times as many works as Vermeer. And Rembrandt had already completed well over 100 paintings by his early forties. So out of Vermeer’s 34 securely attributed paintings, only two are cityscapes. A third cityscape likely existed: an auction record from 1696 mentions a work titled “A View of Some Houses”. Whether that painting still exists is an open question. That also goes for Vermeer himself:

- We do not know of any diary or journal of Vermeer. No letters of the artist are documented and not that many witnesses of the time wrote about Vermeer. What we do know about him comes mostly from notarial records, guild registers and a bankruptcy inventory.

- We also don’t actually know what Vermeer looked like, and there is no securely identified self-portrait of him. A few figures in his paintings have been proposed as self-portraits. Most notably the man in the black beret on the left in The Procuress and the painter seen from behind in The Art of Painting, but none of them can be identified with certainty as his true face.

Vermeer was the second child of Reynier Jansz Vos, a weaver who also ran an inn and traded paintings in Delft. The family later moved to another inn called “Mechelen”, where Vermeer grew up surrounded by the city’s everyday life as well as works of art. After his father’s death in 1652, Vermeer took over the art-dealing business while his mother continued to run the inn, which he would later inherit.

In 1653, Vermeer married Catharina Bolnes, whose mother, Maria Thins, belonged to a well-to-do Catholic family. The couple eventually moved into Maria Thins’s house on the Oude Langendijk, where Vermeer lived and worked for the rest of his life. Around this time, Vermeer also converted to Catholicism. That same year, he registered as a master painter in the Delft Guild of Saint Luke. We don’t know for sure who trained him, but his early paintings show the influence of the Utrecht Caravaggists, as well as artists like Rembrandt. He began his career as a history painter before turning almost entirely to genre scenes paintings of ordinary people doing ordinary things.

Vermeer appears to have balanced painting with art dealing to support a large household. He and Catharina had eleven children known by name, and there may have been others who died early. A small circle of loyal collectors in and around Delft owned several of his works, but Vermeer was never truly wealthy. After 1672, when war hit the Dutch art market hard, his income collapsed. When he died in 1675, his widow had to apply for relief from his debts, and the inventory of their home lists only a modest number of paintings, some by Vermeer himself and some by other artists. For someone whose images feel so precise and present, the outline of his life remains surprisingly fragmentary.1

DETAILS

what do we

actually see?

COMPOSITION

great

detail

A large part of the painting’s immediate impact comes from the diagonal contrast between the dominant house on the right and the clouded sky. That smart trick makes the picture feel lively, open, and strangely inviting.

The house itself is a medieval building with a stepped gable. In Vermeer’s time, this would have already looked somewhat old-fashioned, especially in the city of Delf that had been heavily rebuilt after the great fire of 1536. Vermeer cropped the building by the right edge of the painting so that it seems to continue beyond the frame. This makes the composition more dynamic. The house is clearly the visual focus, but it is not planted in the centre of the canvas. By shifting it to the side, Vermeer gains more room for a quiet, almost isolated field of sky on the left.

Across the surface, the composition is organised in calm horizontal bands: the cobbled street at the bottom, the whitewashed lower walls, the red brick façades, and then the strip of rooftops and sky above. Within this simple structure, Vermeer sets small points of life: two women and two children low in the picture. By painting the bottom of the houses white, he draws the attention to the figures. They are tiny compared to the architecture, but their positions puncture the rigid grid of windows and bricks, guiding the eye gently from left to right.

The result is a view that feels both carefully constructed and completely natural, as if we were standing at a window on the opposite side of the street and happened to catch this exact moment. It is so realistic it almost seems like a photograph.2

TECHNIQUE I

precision

at work

From a technical point of view, The Little Street is anything but casual. Vermeer builds the image slowly in layers over a grey ground, using a very limited but refined colour palette. Examinations revealed earthy reds for the bricks, ultramarine and lead white for the sky, azurite with lead-tin yellow for the green shutters.

The brickwork and stone are painted in thicker, almost tactile strokes, while the sky and figures are handled more thinly, so the facades feel strangely solid and close.

The whole scene is lit by broad daylight instead of dramatic spotlighting: light simply moves across the surfaces and quietly reveals them. Also, recent scientific research shows that Vermeer made several changes in the painting process (see TECHNIQUE III below for details).

The Little Street looks like an effortless time capsule of Delft, but Vermeer really put a lot of thought into it, to make it as special as it is.

TECHNIQUE II

brick

walls

The handling of colour is subtle, particularly in the weathered red brickwork of the facades. Rather than outlining individual bricks in a rigid pattern, Vermeer treats the wall as a vibrating surface of light and texture.

He uses a technique that feels startlingly modern, applying red, ochre and brownish colours to suggest the roughness of the baked clay. On top of that the motar is also cleverly executed: Vermeer didn’t paint lines for the bricks, he painted blobs of light that our eyes interpret as bricks.

To enhance the impression of depth, perspective, light, and realism, the technique shifts slightly across the different walls. While the main house is rendered with relative precision and a focus on detail (3), the house on the left is distinguished by a faster, rougher brushstroke (2). Finally, for the houses in the background, the brickwork is merely suggested rather than fully elaborated (1).

TECHNIQUE III

scientific imaging

Like many of Vermeer’s paintings, The Little Street has been scientifically examined several times. To look beneath the surface, researchers used advanced non-invasive imaging ranging from X-rays and infrared reflectography to macro X-ray fluorescence mapping. These methods make it possible to trace changes Vermeer made as he worked on The Little Street. What they’ve uncovered is genuinely fascinating.3

A woman in the alleyway

A key figure of the painting is the seated woman in the doorway on the right side. New imaging techniques revealed that Vermeer originally painted a seated woman in the alleyway right in front of the woman who is standing at the barrel. And they show even more: The woman Vermeer painted in the alleyway resembles the woman currently visible in the doorway. Their clothing, poses, and scale are so similar that the doorway woman appears to be almost a mirror version of the originally seated figure. It seems fair to say that Vermeer „moved“ the woman and placed her in the position where we see her today.

Lets open the door

So if the doorway originally did not contain the woman we see today, was it empty then? Microscopic studies revealed a blue-green underlayer in several areas of the current woman, such as her head and hands. This indicates earlier painting beneath which is very similar to the surface layer of the green window shutters to the left side of the doorway. So what does that mean? Vermeer first painted the house with a closed copper-green door. He later „opened“ the door and moved the woman into the doorway. This was a brilliant decision as it creates a link between the private interior and the public street adding so much depth to the composition.

Late additions

Arguably one of the most charming features of The Little Street are the children playing in front of the house. These children were late additions, they were painted after the foundational layers had dried. The same applies to the famous striking red shutter on the right side of the doorway.

Imaging shows: The red shutter was not reserved in advance. Vermeer painted it over the whitewashed wall. The wall’s earlier paint layers still show through beneath the red shutter, a clear evidence of later modification. An interesting detail: Red shutters appear frequently in works by Vermeer’s Delft contemporaries, particularly Jan Steen and Pieter de Hooch. De Hooch’s painting The Courtyard of a House in Delft from around 1658, perhaps influenced Vermeer’s decision to add this bold red element.

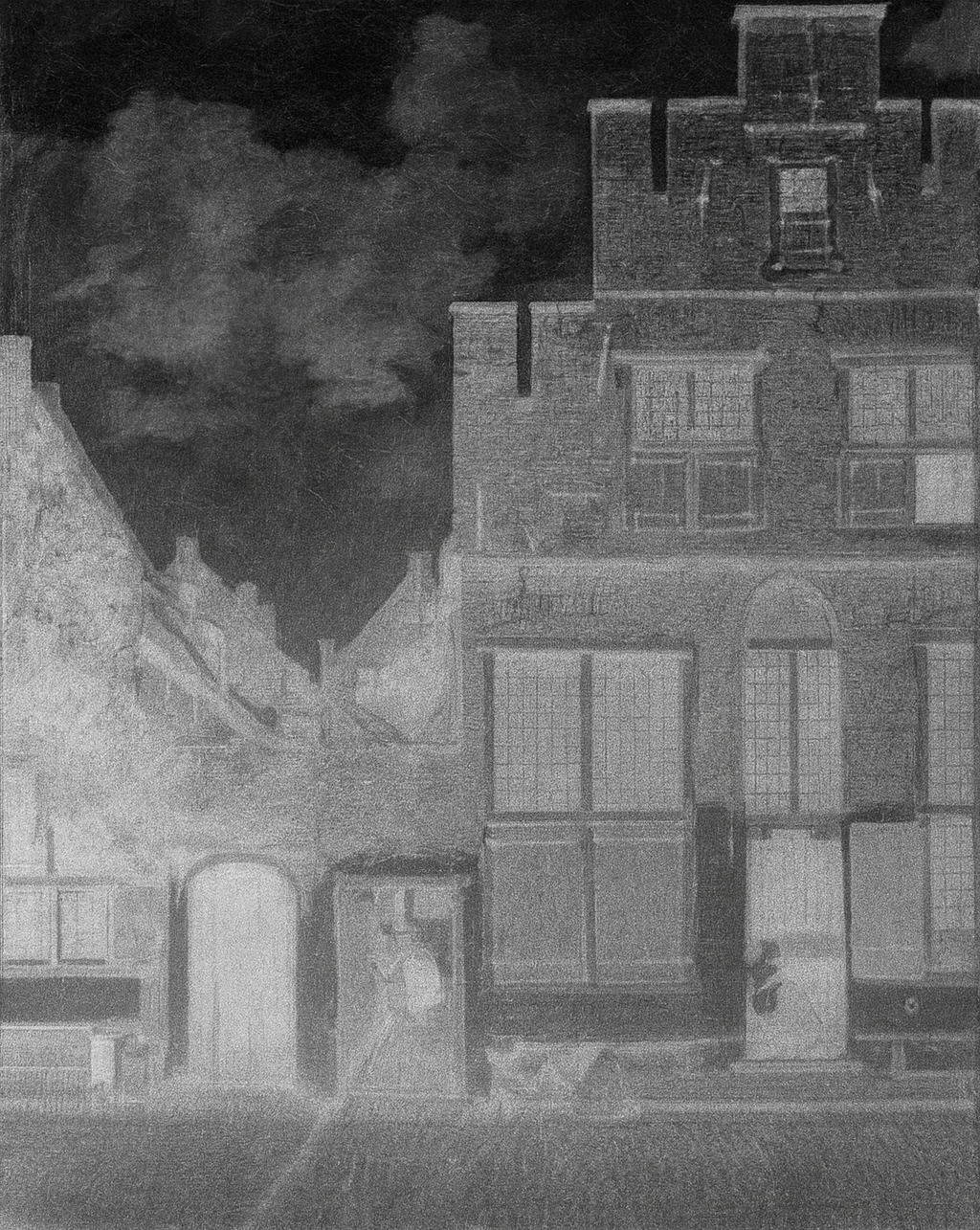

An alternative The Little Street

So, the Rijksmuseum has done something interesting: all of these findings were used to create a digital visualisation of The Little Street that reverses the changes and shows what the painting would have looked like if Vermeer had not altered it.

F. Gabrieli, A. Krekeler, A. van Loon, I. Verslype/Rijksmuseum

Het Straatje, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Public domain (CC0).

Context

finding

the street

For decades one question has clung to The Little Street: are we looking at a real street, a real house? A painting doesn’t show reality, but an artist’s perspective on it. It’s a construction, not a photograph. So can a private building, something unremarkable, something not designed to be remembered, actually be identified?

Over time, no fewer than 15 different locations have been proposed as Vermeer’s inspiration, and every single one comes with reasons to doubt it. But in 2015 a particularly compelling lead surfaced. The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam published findings from research by Frans Grijzenhout, professor at the University of Amsterdam.

A new approach

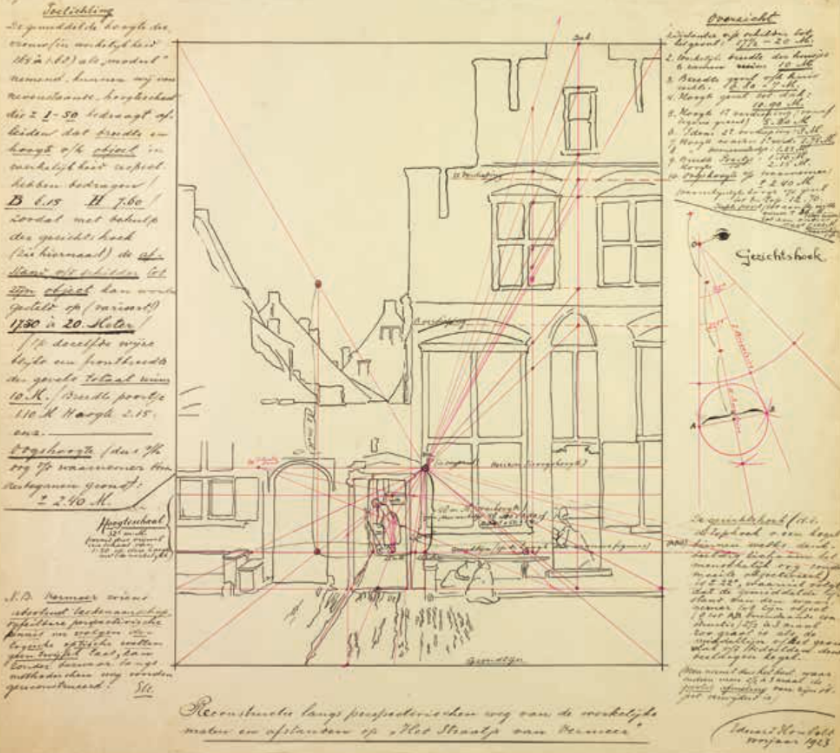

First, Grijzenhout revisited older research to see what could be extracted from the painting itself. One key reference was a perspective study by Eduard Houbolt from 1923. Houbolt concluded that the painter would have been positioned on the first floor roughly 17 to 20 metres from the buildings. Small streets in 17th-century Delft (and in the Netherlands generally) aren’t 17 metres wide, they’re much narrower. Canals, on the other hand, are often wider than 20 metres though there are also narrower canals that could roughly match these dimensions. If a narrow canal is the setting, the steady trickle of water from the alleyway begins to make sense, because such passages often ended at a canal.

As a historian, Grijzenhout knew Delft had a tax register for property owners along the canals. So he went into the archives.

In a register from 1667, he searched for a configuration similar to the painting: two alleyways between two houses. The document records the dimensions of houses and gateways along the canals and lists the tax amounts the residents had to paid. The only place where a comparable situation appears is on a small canal called Vlamingstraat. The owner of the relevant house Vlamingstraat 42 was a woman named Ariaentgen Claes.

Verifying the idea

So there’s only one occasion, one plausible place where the scene could have been. But there’s a catch: Vermeer painted the house on the right in a medieval style, which means it would already have been very old by the mid-1600s. And in 1536 a major fire hit Delft, causing severe devastation and destroying much of the old city centre. A medieval house like this would have been unlikely to survive into the 1650s.

But unlikely doesn’t mean impossible. Grijzenhout searched for early maps of Delft and found a striking clue. A work titled “Plattegrond van Delft na de stadsbrand van 1536” (c. 1620) shows the city’s damage through graphic suggestions of ruins. In it, Vlamingstraat is fairly easy to identify and there’s a surprise: the image marks a medieval-looking house still standing while the surroundings appear damaged by fire. That’s a strong hint that at least one pre-fire building may have survived on Vlamingstraat.

Grijzenhout didn’t stop there. He also looked for an official map of Vlamingstraat. The earliest record he found was a cadastral map from 1823a. At first, that seems too late to matter almost 200 years after The Little Street was painted. So what could it possibly add? In the map, the layout around Vlamingstraat 40 and 42 was, at first glance, surprisingly comparable to what Vermeer shows.

Using this cadastral map as a base, researchers created several studies of the houses on Vlamingstraat and of the buildings behind them in 2D and 3Db,c. They then overlaid these models onto the painting. The results were striking: the perspective, dimensions, and rooflines all aligned convincingly with Vermeer’s view. Grijzenhout concluded that Vermeer could plausibly have seen a scene at Vlamingstraat 40 and 42 in the 1650s that resembled the painting though coincidence can’t be ruled out.

The Neighbourhood

The setting fits. But how do we know whether Vermeer actually went to Vlamingstraat, whether he could have stood there and seen houses 40 and 42 with his own eyes? Now, this is where it gets really interesting.

Remember the woman who owned the house at Vlamingstraat 42, Ariaentgen Claes? She was a widow with children, making and selling homemade food to earn a living and to pay off the house she bought in 1645. Her full name appears as Ariaentgen Claes van der Minne—and she was the (half-)sister of Reynier Jansz. That could be the missing piece of the puzzle. Reynier Jansz was Vermeer’s father, which makes Ariaentgen Claes his aunt. This connection is striking. And it doesn’t stop there: Vermeer’s older sister Gertruy reportedly lived at Vlamingstraat 61, directly across the street. Yes, that true: Vermeers aunt and sister lived in the same Neighbourhood, the Vlamingstraat. So it seems highly likely that Vermeer visited the street and may even have known it well. Many historians and Vermeer specialists support Grijzenhout’s argument4, that Vermeer did not invent this scenery. And while the identification of Vlamingstraat 40–42 is widely discussed and endorsed by the Rijksmuseum, alternative theories about the painting’s precise topography remain in circulation.

FINAL NOTE

portrait

of home

We come to the end of our exploration and we reached the final address Vlamingstraat 40 and 42.

The painting has transformed from a „naive“ study of houses into something deeply personal. We are no longer just seeing a masterpiece of a Dutch master, we may be looking at the neighborhood of Vermeer’s life. Knowing that the woman in the doorway might be his aunt , and that his own sister lived just across the street, changes the „vibrating surface“ of those red bricks. The „opened“ door and the late addition of playing children could very well not just be technical choices to create depth but the finishing touches on a „family portrait“ disguised as a cityscape.

If we know so little of Vermeer’s inner life, it may be precisely this painting that brings us closest, not through a direct statement, but through proximity, familiarity, and the quiet weight of belonging.

FOOTNOTES

- Bakker, Piet. “Johannes Vermeer” (2017). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 4th ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Elizabeth Nogrady with Caroline Van Cauwenberge. New York, 2023–. https://theleidencollection.com/artists/johannes-vermeer/ (accessed November 30, 2025). ↩︎

- Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/stories/one-hundred-masterpieces/story/the-little-street (accessed December 14, 2026) ↩︎

- Dorothy Mahon, Abbie Vandivere, and Ige Verslype, Closer to Vermeer: New Research on the Painter and His Art(London: Thames & Hudson, 2025), 70–74. ↩︎

- Grijzenhout, F. (2018). Het Straatje van Vermeer: een plaatsbepaling. Bulletin (KNOB) , 117 (1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.7480/knob.117.2018.1.2014, License CC BY (accessed on November 30, 2025) ↩︎